In this blog post, we will dive deep into two of the indicators – housing cost burden for both renters and homeowners – and highlight key findings, as well as provide an analysis of the landscape underlying the indicator and a discussion of potential policy solutions.

Key Findings

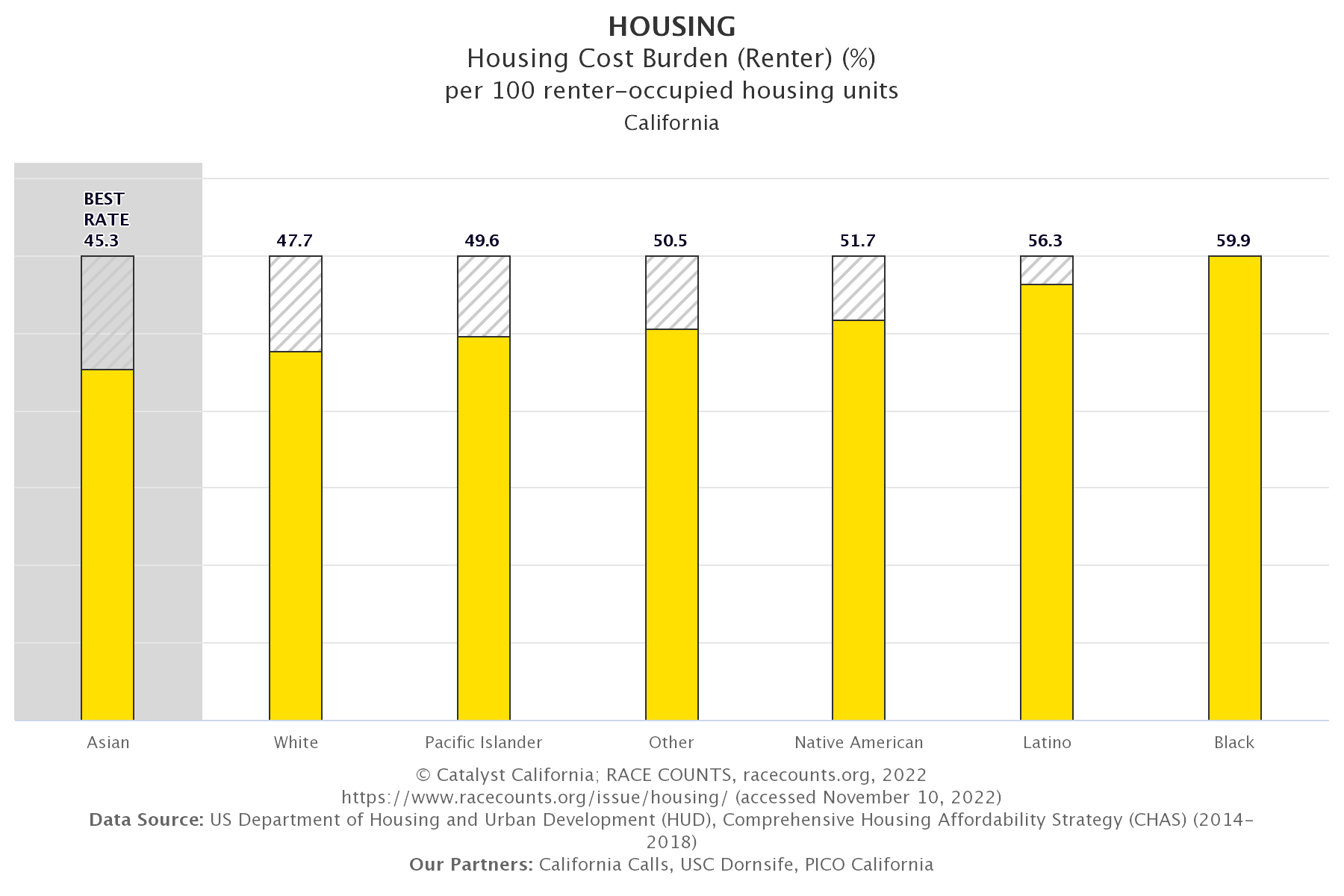

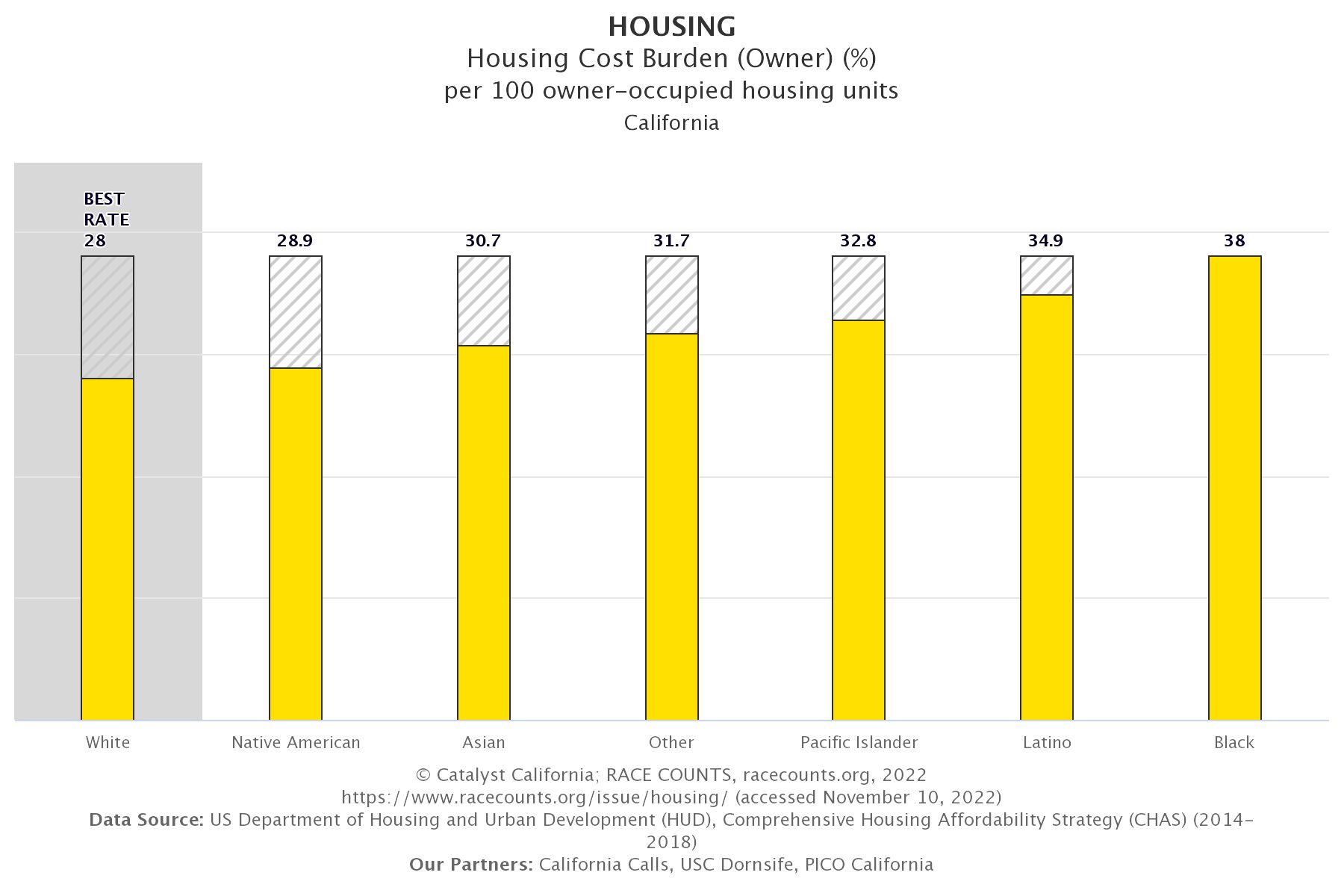

A person is considered housing cost-burdened if they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs. According to updated RACE COUNTS data, across the state 51.7 percent of renter households and 30.4 percent of homeowner households are housing cost-burdened. Among renter households, Latinx and Black renter households have higher cost burden rates compared to the state average. Among owner-occupied households, non-Latinx other, non-Latinx Pacific Islander, Latinx, and non-Latinx Blacks have higher cost burden rates compared to the state average.

When examining the data through a geographic lens we see that, in general, the majority of the more populous counties have high housing cost burdens and relatively little differences in housing cost burdens between racial and ethnic groups. In these counties housing costs are so high that many renters and homeowners across racial and ethnic groups are cost burdened, which would result in limited racial disparity. For the renter housing cost-burden indicator, we find that Imperial County has the highest disparity (i.e., greatest difference between racial groups) and Butte County has the lowest outcomes (i.e., highest cost-burden rate). For the homeowner housing cost-burden indicator, we find that Modoc County has the highest disparity and Alpine County has the lowest outcomes.1 Los Angeles County, the most populous county in the state, has the second worst owner cost burden outcomes rank and the sixth worst renter cost burden rank among all California counties.

Root Causes

History of racial discrimination

Any discussion of the root causes of racial inequities in housing must start with a discussion of the historical, systemic discrimination that people of color, and Black communities in particular, have faced in housing. The settlers who colonized the United States of America did so by forcibly taking land from Native peoples and displacing them. In addition, systemic racial discrimination placed limits and prohibitions on people of color’s ability to own property and promoted racial segregation.

During the Great Depression, the federal government made a push to promote housing production and home ownership. As part of this effort the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) insured home mortgages. However, the FHA engaged in the discriminatory practice of “red-lining” where they deemed neighborhoods with high concentrations of Black residents as high risk or unstable. As a result, these neighborhoods and their residents were less likely to benefit from the pro-housing programs and policies of the time. Red-lining and other practices such as racial covenants were key factors in the creation of racially segregated, high-poverty communities. Through “urban renewal” policies and systemic disinvestment, the government actively disadvantaged, and in some instances destroyed, communities of color. The legacy of this long history of institutional racial discrimination in housing is alive and well in the current housing landscape.2

Lack of affordable housing units

One contemporary root cause of the housing affordability crisis in California is the lack of affordable housing units. According to the recent state housing plan, California must produce an estimated 2.5 million housing units, including at least 1 million affordable units, by 2030 to meet the state’s housing needs.3 When the need for affordable housing is so much greater than the existing supply, this puts upward pressure on the cost of housing – making it more likely that renters and homeowners will spend a frequently unsustainable amount of their income on housing. Factors that limit affordable housing production include a lack of funding, local opposition to affordable and dense housing, the high cost of land, and the high cost of production.

Commodification of housing

In the U.S., housing is largely considered an asset and a mechanism to build wealth. Given the high and increasing value of housing in California, many corporate and foreign interests have purchased housing to secure a financial windfall. Researchers estimate that corporations own approximately 17 percent of California’s housing supply.4 During the Great Recession when many low-income homeowners and homeowners of color lost their homes, many corporate interests saw a financial opportunity and acquired many of those units. These corporate interests‘ primary motivation is to make the highest return on their investment and, as such, will engage in speculative practices and charge as much as possible to rent or own their units.

Lack of tenant protections

The housing system privileges property owners and provides little support for tenants. Relative to property owners, tenants have fewer legal rights and protections. For example, while the state recently passed a rent cap and many local jurisdictions have passed rent control policies, there are concerns that the current policies are insufficient and that despite these policies, many low-income tenants and tenants of color will likely see rent increases that they are unable to afford. Without sufficient protections, tenants lack the power and institutional mechanisms necessary to combat the practices and policies that enable the high and increasing housing costs in the state.

Potential Policy Solutions

To address the housing affordability crisis we should increase affordable housing production, promote affordable housing preservation, and expand tenant protections. Affordable housing production and preservation would help to increase the number of affordable housing units available, which in turn would lower housing costs and, subsequently decrease the number of renters and homeowners who are housing cost-burdened. This would be of particular benefit to communities of color who, as we described above, are particularly likely to be housing cost-burdened. Expanded tenant protections will help individuals who are vulnerable for eviction and housing instability from falling into homelessness, which disproportionately impacts people of color.5

Affordable housing production

As mentioned earlier, California faces a significant shortfall in affordable housing units that falls well below the state’s need. The state’s low-income communities and communities of color will continue to face significant housing cost burden until the affordable housing shortfall is addressed. To address it, we must increase the funding allocated to affordable housing production. From 2013 to 2018, California’s average annual funding of affordable housing decreased from $1.3 billion to less than $500 million.6 The state and local jurisdictions would greatly benefit from permanent, significant funding sources that would support affordable housing production. This, in part, is why Catalyst California has endorsed Measure ULA in Los Angeles, which would raise an estimated $900 million annually with a portion of the funds going to supporting affordable housing development (as of this writing, it appears that L.A. voters have approved the measure).7

In addition to increasing funding for affordable housing production, it is important to make it easier and cheaper to produce affordable housing. These efforts could include ending exclusionary zoning and adopting land use reforms, such as opening up more public land for affordable housing. As we seek to increase affordable housing production, we must also ensure that these efforts do not cause the displacement of low-income residents and residents of color.

Affordable housing preservation

In addition to producing new affordable housing units, we must preserve existing affordable housing units. Each year the state loses a substantial number of affordable housing units due to expiring affordability covenants and because affordable housing units are converted into condominiums. One way to combat the loss of affordable housing units is the passing of Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) and Community Opportunity to Purchase Act policies that provide a chance for tenants and qualified non-profits to purchase property when it comes up for sale or demolition/discontinuance of use. Furthermore, efforts to promote community ownership and alternative ownership models such as Community Land Trusts and housing cooperatives should be explored as a means of preserving housing affordability.

Tenant protections

There are a number of policies that could expand tenant protections and level the playing field between property owners and tenants. As mentioned earlier, the state does have a statewide rent cap and many local jurisdictions have rent control, but these policies can be strengthened to cover more tenants and to provide stronger protections. For example, repealing or reforming the Costa Hawkins Rental Housing Act8, would provide local jurisdictions greater flexibility to expand and strengthen their rent control policies. Other key tenant protection policies to consider are a tenant right to counsel and just cause eviction. A strong right to counsel policy would guarantee that low-income tenants facing eviction receive legal advice and representation in court and prevention and pre-litigation services including emergency rental assistance. Just cause eviction policies would ensure that tenants cannot be evicted without a fair reason.

Policies should not be limited to those that protect tenants from unaffordable rents and eviction but also those that protect tenants from displacement and support tenants who are displaced. During the pandemic, the state and many local jurisdictions worked to support vulnerable tenants through efforts like enacting eviction moratoriums though many of these protections have sunset or will soon end and may have had limited effectiveness. For example, recent reporting suggests that landlords were still seeking to evict tenants in Los Angeles despite an official eviction moratorium.9

Urgency of Action

Polling from the Public Policy Institute of California finds that homelessness and housing costs and availability rank as the second and third most important issue facing the state, respectively.10 Recognition of an issue is a necessary but insufficient condition to addressing it. The recognition must also come with the data and knowledge to see who is most impacted by the issue and an analysis of the issue’s underlying landscape and potential solutions. This blog aims to provide both data and analysis that will inform our understanding of racial inequities in housing and potential paths forward to eliminating these inequities. By eliminating these inequities not only would there be progress in addressing the affordable housing crisis impacting Californians of color, there would also be progress in the many Californians of color’s economic circumstances such that they would have more financial resources to allocate to things like health care, education, and child care.

- It is important to note that counties with smaller populations are more likely to appear in the top or bottom of county rankings.

↩︎ - Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2018. ↩︎

- Walker, Harrison. “California’s Housing Shortage Is Not for Lack of Money.” Los Angeles Magazine, August 1, 2022. https://www.lamag.com/citythinkblog/californias-housing-shortage-is-not-for-lack-of-money/. ↩︎

- Chapple, Karen, David Garcia, Eric Valchuis, and Julian Tucker. “Reaching California’s ADU Potential: Progress to Date and the Need for ADU Finance.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation. University of California Berkeley, August 2020. https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/ADU-Brief-2020.pdf. ↩︎

- “Who Is Experiencing Homelessness in California?” California Budget and Policy Center, March 1, 2022. https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/who-is-experiencing-homelessness-in-california/. ↩︎

- Rothwell, Jonathan. “Land Use Politics, Housing Costs, and Segregation in California Cities.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation. University of California Berkeley, September 2019.http://californialanduse.org/download/Land%20Use%20Politics%20Rothwell.pdf. ↩︎

- Yes on Measure ULA. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://unitedtohousela.com/. ↩︎

- The Costa Hawkins Rental Housing Act is a statewide law that was passed in 1995 that established limits on the types of rent control policies that cities are able to enact. ↩︎

- Dillon, Liam, and Ben Poston. “Despite Protections, Landlords Seek to Evict Tenants in Black and Latino Areas of South L.A.” Los Angeles Times, June 18, 2020. https://www.latimes.com/homeless-housing/story/2020-06-18/despite-protections-landlords-attempting-to-evict-tenants-in-south-l-a-black-and-latino-neighborhoods-data-shows. ↩︎

- Baldassare, Mark, Dean Bonner, Rachel Lawler, and Deja Thomas. “PPIC Statewide Survey: Californians and Their Government.” Public Policy Institute of California, October 5, 2022. https://www.ppic.org/publication/ppic-statewide-survey-californians-and-their-government-september-2022/. ↩︎